All too often, we use weak fixes to prevent future significant problems. Do you know how to write effective corrective actions?

How to Write Effective Corrective Actions

A well-written corrective action clearly defines how to modify a process, or alter a piece of equipment, in order to reduce the potential for future human error or equipment failure. For example, when we modify a process, we can add, or delete, one or more process steps.

Also, we might rewrite the standard operations procedure so it is more usable. All too often however, we attempt to use weak fixes to prevent future problems of a significant nature. How many of your staff know how to write effective actions?

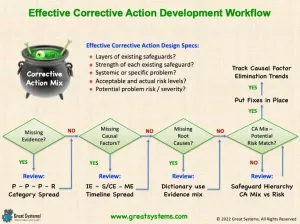

Do you use the TapRooT® root cause analysis process to find root causes and write effective corrective actions? If so, my corrective action creation workflow may help

How Effective are the Corrective Actions You Write?

To effectively modify the work environment or equipment, we must ensure our corrective actions contain an adequate level of detail. When leaders make changes of this nature and fail to include sufficient detail, it can actually worsen the problem from a human-machine or human versus work environment perspective.

At the same time, many corrective actions are too general in focus. Worse yet, they might fail to define an actual process or equipment change.

A Possible Workflow for Writing Effective Corrective Actions

Do you use the TapRooT® root cause analysis process to find root causes and write effective corrective actions? If so, my corrective action creation workflow may help. In this process, there are multiple points where an incomplete investigation can result in less than effective fixes. However, you can avoid such gaps.

First, design the investigation process to capture the right mix of evidence. Second, teach investigators how to effectively use this evidence to find key causal factors, root causes, and ultimately, effective fixes. Finally, install effective corrective and preventive actions to help minimize the chance of problem return.

Define Expectations for Effective Corrective Action Design

Once the new rules and direction are set, leaders must define and execute a systematic means to communicate these procedural changes to the workforce. A well-written corrective action should also define what formal mechanisms will be used to gauge (1) if the change was put in place and (2) if the change was effective.

The CAPA Guidelines perhaps provide the best definition of a corrective action. These guidelines state that “documentation for a corrective action provides evidence that the problem was recognized, corrected, and proper controls installed to make sure that it does not happen again.”

How to Build a Corrective Action Burger

When I teach people how to write corrective actions, or when I write them myself, I use the ‘corrective action burger’ approach. This three-sentence approach helps me make sure that I include key things in the corrective action I write.

First, I provide a general statement of the key change to make and its expected benefits. All too often, this ‘top bun’ sentence is the only content people include in the corrective actions they write.

For example, ‘Encourage all staff to follow safety rules’ is NOT a well-written fix. HOW will you consistently make this happen? Change how work is done each day to make your improvements last.

Then, I provide sufficient detail on the change to be made. Typically, two to three key features of the change is adequate. This sentence provides the ‘meat’ of the burger.

Finally, I describe how to roll out the change to all stakeholders. This ‘bottom bun’ helps ensure certain groups are not forgotten as you deploy your key changes.

Why Writing Effective Corrective Actions Matters

Effective corrective actions eliminate or minimize the reoccurrence of the ‘at risk’ behaviors that were part of the incident. If you ask to what degree will the fix take away, or minimize, those behaviors, you can quickly determine the potential impact of a given fix. Also, you can assess the change in risk level once the likelihood of error, and possibly the severity of error, have been reduced.

In general, leaders expect too much behavior change that lasts from weak fixes like reprimands, reminders, and more rules. A certain percentage of people will change for good when you ask them to. However, others need system changes to help guide, encourage, and reinforce their use of the new behaviors.

What are your favorite fixes? How do you teach people to both identify and write more effective corrective actions? Odds are that if you improve this process alone, you could save significant time and money. Plus, you will reduce the potential for process errors.

EXPLORE MORE: Workplace Safety Best Practices

Step #1: Review your most recent 50, or so, root causes and corrective actions

What patterns, biases, and gaps do you see? Do you have favorite root causes and fixes? Are there certain types of root causes and fixes you don’t see very often on the list? Conduct periodic audits of your corrective action quality to help identify bias and weak writing habits.

Do you provide job aids that prompt your investigators to ask a well-rounded set of questions? If not, it is likely that bias is evident in your root cause analysis results.

Similarly, people write corrective actions out of habit. They often fail to ensure the relative strength of the fix matches the potential severity of the problem. Also, they may only know of certain types if fixes. For example, human factors improvements are often inexpensive, but unknown.

Step #2: Require the effective completion of a corrective action writing class

This class does not have to be fancy, expensive, or even live. However, it should include practice writing effective corrective actions.

Have one or more coaches available to provide feedback as the practice corrective actions are written. Support this in-class practice with the use of examples of both well-written and poorly written fixes. This use of examples helps define post-class expectation standards.

Step #3: Evaluate ‘fix mix’ strength against potential problem severity to ensure a match exists

All too often, we base our mix of necessary corrective actions on what actually did occur versus what the outcome might have been. The difference between a near miss and a fatality is often not that much.

We should not dilute our mix of fixes just because we got lucky in this instance. We should always ask “What could have been the outcome?”

DISCOVER MORE: Process Improvement Strategies

Step #4: Push for creative, engineered fixes

One way to do this is to always recommend at least one engineered fix of some fashion in any mix of changes you propose. Also, work your way down the hierarchy of controls as you look for solutions. Such a practice helps you consistently push for engineered fixes.

Often, we can make human factors improvements without the need for a significant investment. Examples include the use of color codes, RFID asset tags, and tablet-based behavior cues and triggers.

What options exist to help eliminate or minimize the potential for hazard or defect exposure? Can you better protect the customer or the patient from potential hazards or errors? Can we do better guard the internal or external customer from the potential problem?

Step #5: Expect ‘high risk’ behavior observation trends to reflect corrective action effectiveness

The best way to tell the degree to which your corrective actions are working or not is to look for ‘high risk behaviors’ during daily process operation. What are your work process error rates? Have the error or failure rates decreased?

All too often, we only sample workplace error rates. Few work team leaders track key daily process errors and trend these errors over time.

Instead, they focus on preventing bad things from happening. In the mean time, the incremental cost of the daily errors accumulate to higher and higher levels.

Step #6: Reduce the holes in your current safeguards before you add new ones (more slices of cheese)

Too few companies measure safeguard effectiveness. In turn, they don’t know the relative degree to which each safeguard type is effective. They assume that the safeguards in place work somewhat, but they need more of them to prevent the current rate of errors.

LEARN MORE: Buy my “Error Proof – How to Stop Daily Goofs for Good” book at Amazon.com

How Do You Know When Your Corrective Actions are Effective?

In reality, much opportunity exists for safeguard improvement if you use best practices as a guide in most companies. Instead of spending more time and money trying to prevent errors, spend the existing time and money you now contribute to this purpose differently.

Once a corrective action has been written, you should always question the degree to which it will be effective. It is even more important to assess the relative impact of the set of corrective actions that you will recommend and implement.

Will this mix of fixes significantly reduce the risk from future human errors or equipment failures of this type?

Keep improving!

Kevin McManus, Chief Excellence Officer, Great Systems

WATCH over 50 kaizen and workplace health improvement videos on my Great Systems YouTube channel.

CHECK OUT my ‘Teach Your Teams’ workbooks on Amazon.com

LIKE Great Systems on Facebook

© Copyright 2024, Great Systems LLC, All Rights Reserved