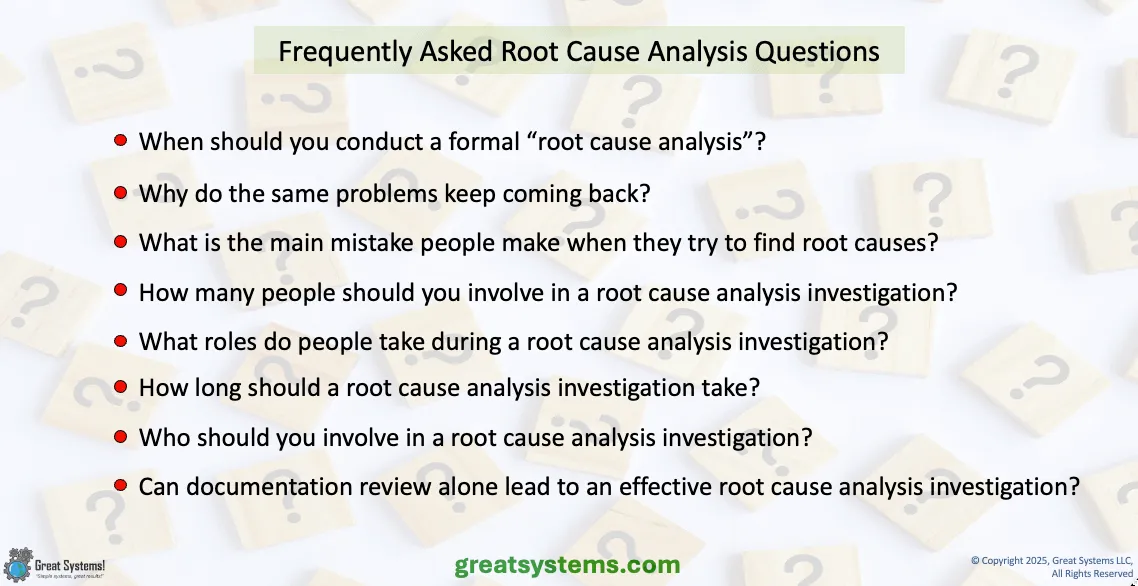

Root Cause Analysis FAQs

What Root Cause Analysis FAQs Do You Hear People Ask?

How do you find root causes? How effective are the root cause analysis questions your problem solvers ask? What are some of the root cause analysis FAQs you commonly hear?

In order to improve ANY process, you must find and minimize the root causes of process waste. Most organizations would say that they know this. They could easily show you how they invest lots of time and money over time in attempts to do this. What they might struggle to do, however, is demonstrate to you the effectiveness of their current root cause analysis process.

The following root cause analysis questions represent those that I have been asked to comment on over the years:

When should a formal “root cause analysis” be conducted?

To effectively answer this question, we need to determine what is meant by the term ‘formal.’ Most people consider root cause analysis to be formal in nature if some tool, or set of tools, is used to help guide people towards the root causes of a problem (as opposed to simply standing around and relying on opinion). My personal definition goes a little further however.

To me, a root cause analysis process is not formal unless that process uses facts to validate the selected root causes. Ideally, the same facts help guide the problem solvers towards a comprehensive list of possible root causes early in the process. Often, the list of possible root causes itself is much less than adequate.

It could be that the belief systems, opinions, or knowledge base of the problem solver does not consider a sound list of root cause possibilities. If your list of possible root cause options is too short, you may consider human error and equipment failure to be at the 'root cause' level.

To me, a root cause analysis process is not formal unless that process uses facts to validate the selected root causes. Ideally, the same facts help guide the problem solvers towards a comprehensive list of possible root causes early in the process. Often, the list of possible root causes itself is much less than adequate.

It could be that the belief systems, opinions, or knowledge base of the problem solver does not consider a sound list of root cause possibilities. If your list of possible root cause options is too short, you may consider human error and equipment failure to be at the 'root cause' level.

Effective root causes analysis helps identify the missing or failed safeguards that heighten the risk of human performance problems or equipment failires. How do you measure safeguard effectiveness?

WATCH over 50 kaizen and workplace health improvement videos on my Great Systems YouTube channel.

WATCH over 50 kaizen and workplace health improvement videos on my Great Systems YouTube channel.

When should “root cause analysis” be conducted on an equipment failure event?

Ideally, one should analyze all equipment problems. Unfortunately, few organizations, if any, have the resources to pursue this ideal in the short term. In turn, we must attack equipment problems from two perspectives. First, formally analyze all 'major' problems. Reference acceptable risk and error levels, along with cost thresholds, to help determine what ‘major’ means.

Secondly, capture all 'significant' downtime problems (again, define the significance threshold) in a database for subsequent Pareto analysis. Finally, use formal root cause analysis on the biggest bar of the Pareto chart, just as you would do for a singular equipment problem.

Secondly, capture all 'significant' downtime problems (again, define the significance threshold) in a database for subsequent Pareto analysis. Finally, use formal root cause analysis on the biggest bar of the Pareto chart, just as you would do for a singular equipment problem.

Why do my problems keep coming back?

As root cause analysis process formality and soundness of design increases, your problems should decrease over time. Conversely, if you choose to use root cause analysis tools such as fishbone diagrams or the 5 Whys that rely more on opinion, you may compromise the results of your root cause analysis efforts. It will not matter if you use these tools in a formal manner or not.

In too many organizations, problems repeatedly come back. Reasons for repeat problem return include ineffective root cause analysis and weak corrective actions. Also, people often fail to validate the root causes they select with facts. Finally, too many problem solvers rely on a less than adequate list of possible root causes.

In too many organizations, problems repeatedly come back. Reasons for repeat problem return include ineffective root cause analysis and weak corrective actions. Also, people often fail to validate the root causes they select with facts. Finally, too many problem solvers rely on a less than adequate list of possible root causes.

What is the main mistake people make when they ask root cause analysis questions to diagnose a problem?

The most common mistake people make when they search for the root cause of a problem is to assume that the human errors or equipment failures they find are the actual problem's root cause or causes. Think about it. What does the media say the main cause of airline accidents is? Most people guess it - pilot error.

We fail to look for the systemic design or execution flaws that increase the likelihood of human error or equipment failures. Instead, we blame the person, or fix the equipment. We think that our problems are solved. Unfortunately, the problems often come back - again and again. In turn, the time we invest in our root cause analysis efforts ends up as waste. Plus, frustration arises when the same old problems come back to haunt us.

From a TapRooT® root cause analysis perspective, pilot error is what we call a causal factor. Causal factor definition begins the root cause analysis process - they are not the end point. A small percentage of teams do search for the system problems that led to a human error or equipment failure, but most do not.

However, in TapRooT® root cause analysis, we analyze each casual factor for possible root causes. Use of facts from the problem investigation effort, along with root cause analysis questions from the TapRooT® dictionary, help find the actual systemic problems. These are the true problem root causes.

We fail to look for the systemic design or execution flaws that increase the likelihood of human error or equipment failures. Instead, we blame the person, or fix the equipment. We think that our problems are solved. Unfortunately, the problems often come back - again and again. In turn, the time we invest in our root cause analysis efforts ends up as waste. Plus, frustration arises when the same old problems come back to haunt us.

From a TapRooT® root cause analysis perspective, pilot error is what we call a causal factor. Causal factor definition begins the root cause analysis process - they are not the end point. A small percentage of teams do search for the system problems that led to a human error or equipment failure, but most do not.

However, in TapRooT® root cause analysis, we analyze each casual factor for possible root causes. Use of facts from the problem investigation effort, along with root cause analysis questions from the TapRooT® dictionary, help find the actual systemic problems. These are the true problem root causes.

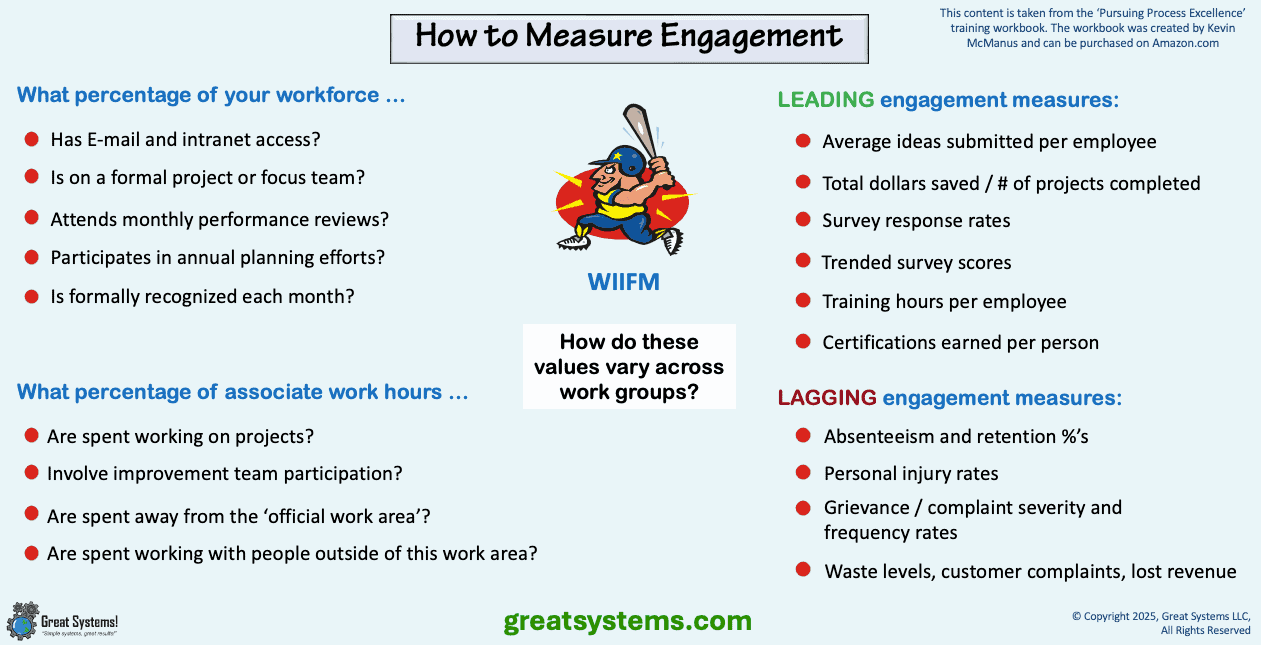

LISTEN to my 'How to Increase Work Team Engagement' Real Life Work podcast

How many people are normally involved in a root cause analysis investigation?

The number of people one involves in an investigation depends primarily on two factors. What magnitude of problem will you investigate? What level of investigation quality do you desire? Keep in mind that you use the majority of your investigation time to collect evidence and other data (usually at least 75%).

Typically, we interview the person, or persons, who were injured, made an error, or discovered an equipment problem. Second, we talk with any witnesses who were in the work area. Then, you ask questions of subject matter experts (SMEs). I have found that the number of subject matter experts you choose to interview affects the 'total people' number AND the investigation quality the most.

High levels of investigator skill can reduce the number of SMEs you need to involve to some degree. For example, two key skills are one's ability to ask a lot of great questions and also keep a very open mind. However, the same rule of thumb still applies – more human input, better results. Additionally, the amount of non-interview data you need to collect affects the number of people you ultimately involve.

The final factor that helps determine how many people to involve is the time available to complete the investigation. Do you need an analysis and a report quickly? If so, you need to throw more resources at the investigation. If you have the luxury of taking six months to analyze a relatively minor problem, one competent person could possibly handle it.

Typically, we interview the person, or persons, who were injured, made an error, or discovered an equipment problem. Second, we talk with any witnesses who were in the work area. Then, you ask questions of subject matter experts (SMEs). I have found that the number of subject matter experts you choose to interview affects the 'total people' number AND the investigation quality the most.

High levels of investigator skill can reduce the number of SMEs you need to involve to some degree. For example, two key skills are one's ability to ask a lot of great questions and also keep a very open mind. However, the same rule of thumb still applies – more human input, better results. Additionally, the amount of non-interview data you need to collect affects the number of people you ultimately involve.

The final factor that helps determine how many people to involve is the time available to complete the investigation. Do you need an analysis and a report quickly? If so, you need to throw more resources at the investigation. If you have the luxury of taking six months to analyze a relatively minor problem, one competent person could possibly handle it.

What roles do people take during a root cause analysis investigation?

The roles that people play as part of an investigation closely link to the (1) types of information one needs to collect (interviews, document collection and review, site visit and analysis, and video review) and (2) the steps of the investigation process itself. One person, of course, would serve as the lead of the investigation effort. Others might serve as interviewers and data collectors. Some people may do little more than answer root cause analysis questions or provide documentation.

If you use a team approach to collect investigative information and develop corrective actions, you also need a skilled team facilitator to avoid wasting valuable group time. Some people, for example, can effectively manage a project on their own. However, they may not have the skills necessary to manage group dynamics or group conflict. A team approach can waste a lot of resources without sound facilitation. Also, the group can lose confidence in the investigation effort without an effective group process.

If you use a team approach to collect investigative information and develop corrective actions, you also need a skilled team facilitator to avoid wasting valuable group time. Some people, for example, can effectively manage a project on their own. However, they may not have the skills necessary to manage group dynamics or group conflict. A team approach can waste a lot of resources without sound facilitation. Also, the group can lose confidence in the investigation effort without an effective group process.

How long will a root cause analysis investigation normally take?

Three primary factors affect the amount of time one needs to complete an investigation. First, the magnitude of the problem under investigation affects investigation scope. Also, the skills of the investigator and the timeline for investigation completion influence this value. The worst case scenario would involve a person with poor investigation skills who wants to solve a big problem in a short amount of time.

Often, TapRooT® instructors say that it can take as much as a week to thoroughly investigate a lost time incident or significant environmental spill. Major problems, such as refinery fires or fatalities, could take weeks or months. You can analyze smaller problems, such as a person put the wrong label on a box of product, in a few hours.

One key factor that drives your ability to do good root cause analysis is the ability to collect a broad set of facts in a concise amount of time (before the evidence changes too much). Interview findings provide only a portion (less than half) of the facts you need to find the systemic root causes of a given problem. Site assessment, document analysis, and video review (if available) are also key. You can cut the investigation cycle time down with fewer facts. However, you may miss root causes.

Most importantly, you must consider the amount of investigation resources available in a given period of time in order to effectively answer this question. For example, it may take 40 people-hours to complete an investigation. If the investigation team can only devote a total of ten hours a week to the investigation effort, it will take 4 weeks to complete the investigation. That is, if they use this time wisely.

Often, TapRooT® instructors say that it can take as much as a week to thoroughly investigate a lost time incident or significant environmental spill. Major problems, such as refinery fires or fatalities, could take weeks or months. You can analyze smaller problems, such as a person put the wrong label on a box of product, in a few hours.

One key factor that drives your ability to do good root cause analysis is the ability to collect a broad set of facts in a concise amount of time (before the evidence changes too much). Interview findings provide only a portion (less than half) of the facts you need to find the systemic root causes of a given problem. Site assessment, document analysis, and video review (if available) are also key. You can cut the investigation cycle time down with fewer facts. However, you may miss root causes.

Most importantly, you must consider the amount of investigation resources available in a given period of time in order to effectively answer this question. For example, it may take 40 people-hours to complete an investigation. If the investigation team can only devote a total of ten hours a week to the investigation effort, it will take 4 weeks to complete the investigation. That is, if they use this time wisely.

Who should you involve in an investigation (level of organization)?

The answer to this question is largely dependent on (1) the culture of the organization involved and (2) the type of involvement you are talking about. Ideally, you should involve a cross section of people from different departments and different levels in the organization. You get better results when you involve this mix of people. This is due to the fact that you are accessing a greater variety of perspectives and skill / knowledge levels.

Unfortunately, too many organizations have cultural issues that make it difficult to involve this mix of people. I have seen companies that don't involve front line people because management does not value their opinion. I have seen other cases where conflict is the result when certain groups are brought together in a room. Finally, the lack of a skilled facilitator makes it tough to get good group results, in general, when a mix of departments is brought together.

Culture aside, there is little excuse to not involve this mix of people from an interview perspective. You might not be able to have them work together in a room to build a Snapchart or develop corrective actions. You should always be able to ask them questions, even if you have to do it one-on-one or with a union representative present over the Internet.

Unfortunately, too many organizations have cultural issues that make it difficult to involve this mix of people. I have seen companies that don't involve front line people because management does not value their opinion. I have seen other cases where conflict is the result when certain groups are brought together in a room. Finally, the lack of a skilled facilitator makes it tough to get good group results, in general, when a mix of departments is brought together.

Culture aside, there is little excuse to not involve this mix of people from an interview perspective. You might not be able to have them work together in a room to build a Snapchart or develop corrective actions. You should always be able to ask them questions, even if you have to do it one-on-one or with a union representative present over the Internet.

Should I engage the operators and maintenance people, or do our investigation documents provide enough evidence for analysis?

If you read my response to the “Who should I involve?” question above, you probably can guess what my response here will be. Documentation review is only one piece of the investigation puzzle. You have to talk to people also! When you talk to people, you learn more about how the documentation was completed, interpreted, and acted upon.

Such dialogue helps you clarify how well people understand the documentation. You gain insight into their document use and completion thought processes. You learn more about the things that are tough to capture on paper, such as smells, feelings, sounds, perceptions, and tastes when you talk to people. Finally, as you know, people don’t write down everything they should.

Also, don’t see it as bothering people. Most people want to contribute their thoughts if you request such thoughts in a non-threatening manner and won't use the information against them. Schedule your interviews at a time that is convenient for the person you want to talk to if possible. It has been my experience that people will be more put off if you do not ask them versus if you do.

Such dialogue helps you clarify how well people understand the documentation. You gain insight into their document use and completion thought processes. You learn more about the things that are tough to capture on paper, such as smells, feelings, sounds, perceptions, and tastes when you talk to people. Finally, as you know, people don’t write down everything they should.

Also, don’t see it as bothering people. Most people want to contribute their thoughts if you request such thoughts in a non-threatening manner and won't use the information against them. Schedule your interviews at a time that is convenient for the person you want to talk to if possible. It has been my experience that people will be more put off if you do not ask them versus if you do.